Abstract

Vitiligo is a result of disturbed epidermal melanization with an unresolved etiology and incompletely understood pathogenesis.

Various treatment options have resulted in various degrees of success. Various surgical modalities and transplantation techniques have evolved during the last few decades. Of them, miniature punch grafting (PG) has established its place as the easiest, fastest, and least expensive method. Various aspects of this particular procedure, especially over the difficult areas have been discussed here.

A detailed discussion on the topic along with a review of relevant literature has been provided in this article.

Key Words: Mini grafting, mini punch grafting, punch grafting, vitiligo, vitiligo surgery

Introduction

Many patients respond to standard medical treatment options. However, several patients remain recalcitrant or respond only partially. Any attempt to repigment these resistant patches with conventional medicinal modalities is often unsuccessful and sometimes frustrating, indicating the absence of a melanocytes reservoir, to induce repigmentation. Under these circumstances, melanocyte repopulation of the achromic areas is not possible, unless a new source of pigment cells is placed by surgical methods within the depigmented lesion/s.

Different corrective surgical methods have evolved during the last four decades. Some of these are: Thin Thiersch’s graft, [1] epidermal grafting by suction blister, [2] punch grafting, [3] mini punch grafting, [4],[5] cultured melanocyte grafting, [6],[7] grafting of cultured epidermis, [8]autografting, and PUVA, [9,10] transplantation of autologous cultured melanocytes, [11] single hair transplant, [12] ultrathin epidermal sheets and basal cell layer suspension [13] and mini grafting and NB-UVB. [14]

Among all these, mini punch grafting (PG) is the easiest, fastest, least aggressive, and a technique with minimal expenses.[14]

Test Grafting

Before embarking upon any surgical intervention in vitiligo, a proper assessment of the stability status is of paramount importance. In recent times, this concept has been discussed in detail. [15]

Clinically, stability can be judged by three simple indicators:

- History

- Lack of progression of old lesions and absence of development of any new lesion within a specified period (6 months to 2 years)

- Koebner phenomenon (Kp)

- Absence of a recent Kp either from history (Kp-h) or experimentally induced (Kp-e)

- Test grafting

On the backdrop of persistent incongruity about the minimal period of stability, an attempt was made for the first time by Falabella, in 1995, to fathom the stability before surgery, by introducing a mini grafting test. [16]

The objective of this test was to:

- Establish the stability of the depigmenting process

- Determine a means by which patients could be selected

- Identify patients who may respond to pigment cell transplantation

- Anticipate the response to surgical repair

In the original suggested procedure, a few grafts (1.0-1.2mm) were placed in the centre of the depigmented lesion to be scrutinized. Dressing was done by Micorpore® adhesive tape and kept for a couple of weeks. After removal of the tape, the area was exposed to sunlight for 15 minutes daily, for a period of 3 months. No treatment was permitted during this test period.

All test sites were visualized under Wood’s light. The test was considered positive if unequivocal repigmentation took place beyond 1mm from the border of the implanted grafts. On the other hand, if less than 1mm or no repigmentation was observed the test was considered to be negative.

In some of the biggest series, this evaluation has been termed as ‘test grafting’ (TG) and is found to be a more reliable exercise than the unjustified dependence on the period of stability alone. [14],[17],[18]

Over the years, this ‘test’ has been vindicated and acknowledged as a powerful tool for detecting stable vitiligo, which anticipates the repigmentation success in vitiligo when surgery becomes a therapeutic option.

After proper assessment of the stability status and routine physical examination and investigations, an informed consent is taken from the patient, and the donor and recipient areas are surgically prepared.

- The instruments required are 1.5 or 1.2mm punches, small jeweler’s or graft holding forceps, and a small curved tip scissors.

- The recipient area is prepared first. Two percent lignocaine with or without adrenaline is infiltrated as a local anesthetic.

- To minimize the chance of developing any perigraft halo, the initial recipient chambers are made on or very close to the border of the lesion. The punched out chambers are spaced according to the result of test grafting or at a gap of 5-10mm from each other.

- The donor area is either the upper lateral portion of the thigh or the gluteal area. Punch impressions are made very close to each other so that a maximum number of grafts can be taken from a small area.

- Same sized punches are used for both the donor and recipient areas.

- The grafts are placed directly from the donor (buttock/upper thigh) to the recipient areas. This speeds up the procedure and lessens the chance of infection. Care is taken to ensure that the graft edges are not folded and the tissue is not crushed or placed upside down. The needle of the syringe or the tip of the scissors is used for the proper placement of grafts in the recipient chambers.

- Hemostasis is achieved by pressing a saline-soaked gauze piece over the area.

- For the recipient area, the three layers of dressing from inside to out are: Paraffin-embedded, non-adherent sterile gauze (Jelonet®), sterile Surgipad® , and bio-occlusive Micropore®.

- For the donor area, only Surgipad®and Micropore® are used.

- The recipient area may be immobilized if necessary. Proper instructions for special areas like the lips are necessary. To secure the recipient area, these patients are advised to be on a liquid diet for the first 24 hours, preferably with a straw. Patients are allowed a normal diet after this period.

- Sometimes dressings are opened after 24 hours to look for any dislodgement of grafts. If any are found, they are replaced.

- Finally, after 4 to 7 days, the dressings are removed.[17],[19],[20],[21] [Fig-]

Follow-up and Course of Events

Post-surgery, the patients are exposed to PUVA [9],[10] / PUVASOL (Psoralen plus UVA from Sunlight) [17],[21] or NB- UVB [14] or even kept as such in some studies. [17] The patients are followed up fortnightly for the initial two months and then monthly, until complete repigmentation is achieved.

In the donor site, after healing with secondary intention, minimal superficial scarring is expected and acceptable.

Scabs may fall off from the recipient site within 7-14 days. However, in many instances, there may not be any scab formation. Perigraft repigmentation is expected to start from around 3-4 weeks. [14],[17],[21]

The entire depigmented and grafted area is expected to be completely repigmented within 3-6 months, based on the area of grafting and the body part involved.

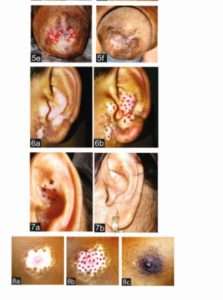

In this article, miniature punch grafting was displayed over upper lip (Fig 2a-2d), eyelids (Fig 3a-3b, 4a-4b) (both upper and lower), male genitalia (Fig 5a-5f), external ear (6a-6b, 7a-7b), nipple (8a-8d).

Complications

Recipient site

- Cobble stoning

- Polka dot

- Variegated appearance and color mismatch

- Static graft (no pigment spread)

- Depigmentation of graft

- Perigraft halo

- Graft dislodgement/rejection

- Hypertrophic scar and Keloid formation

Donor Site

- Keloid

- Hypertrophic scar

- Superficial scar

- Depigmentation/spread of disease

- Contact dermatitis to adhesive tapes

By proper selection of cases most of these complications are entirely avoidable. [5],[19],[20],[21]

Cobble stoning is regarded as the commonest of them all. [14],[17],[18],[21]

It was observed that with time it got corrected in most of the cases. [17] In resistant cases, corrective electrofulguration may be needed. [22]

In this regard it is only apt to conclude that grafting should not be performed with punches more than 1.5mm in diameter. On face and lips, it should be even smaller (1.2mm or 1mm). [14],[23]

Herpes labialis-induced lip leucoderma (HILL) is another unpredictable entity bearing the risk of rejection of grafts. [24],[25],[26],[27]

Advantages

- Easiest, fastest, and least expensive method

- High rate of success with very few preventable/manageable side effects

- Can be performed anywhere, on any site (except angle of the mouth)

Discussion

Surgical correction of vitiligo and other cutaneous achromia have come a long way in the last five decades or so.

However, among all other methods, autologous miniature punch grafting has established its place as the easiest, fastest, safest, and least aggressive means of vitiligo surgery.

When the graft is taken off, the piece of tissue is completely detached from the donor site and then placed on the vascular bed in the recipient holes. From this vascular bed, it derives its blood supply. Initially, the graft adheres to its new bed with the help of fibrin. There is diffusion of nutrients through this fibrinous layer, which keeps the graft alive initially. Within 2-3 days, capillary linkage occurs, with vascularization of the graft. The thinner the graft the denser the capillary network in the superficial dermis, and thus earlier is the process of vascularization. [28]

Acknowledgment

Some figures and tables used in this article have also been used in the following chapter and articles by me and my co-authors.

I would like to properly acknowledge the original source:

- Lahiri K, Malakar S, Sarma N, et al. Repigmentation of vitiligo with punch grafting and narrow-band UV-B (311 nm) a prospective study. Int J Dermatol.2005;45(6):649-55.

- Malakar S, Lahiri K. Spontaneous repigmentation in vitiligo: why it is important? Int J Dermatol. 2006; 45:477-8.

- Malakar S, Lahiri K. Mini grafting for vitiligo. In: Gupta S, Olsson MJ, Kanwar A J, Ortonne JP (Eds).Surgical Management of Vitiligo, 1st edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007;87-95.

- Lahiri K. and evaluation of autologous mini punch grafting in vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54: 159-167

- Lahiri K.Autologous Mini Punch Grafting in Vitiligo. In: Lahiri K, Chatterjee, Sarkar R(Eds). Pigmentary Disorders A Comprehensive Compendium , 1st Jaypee brothers; 2013;241-250

References

| 1. Behl PN. Homologous thin Thiersch’s grafts in treatment of Vitiligo. Curr Med Pract 1964;8:218-21. |

| 2. Falabella R. Epidermal grafting: An original technique and its application in achromic and granulating areas. Arch Dermatol 1971;104:592-600. |

| 3. Orentriech N, Selmanwitz VJ. Autograft repigmentation of leucoderma. Arch Dermatol 1972;105:784-6. |

| 4. Falabella R. Repigmentation of leucoderma by minigrafts of normally pigmented, autologous skin. J DermatolSurgOncol 1978;4:916-9. |

| 5. Falabella R. Repigmentation of segmental vitiligo by autologous mimigrafting. J Am AcadDermatol 1983;9:514-521. |

| 6. Lerner AB, Halaban R, Klaus SN, Moellmann GE. Transplantation of human melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol 1987;89:219-24. |

| 7. Lerner AB, Repopulation of pigmented cells in patients with Vitiligo. Arch Dermatol 1988;124:1701-2. |

| 8. Falabella R, Escobar C, Borrero I. Treatment of refractory and stable vitiligo by transplantation of in vitro cultured epidermal autografts bearing melanocytes. J Am AcadDermatol 1992;26:230-6. |

| 9. Skouge JW, Morison WL, Diwan RV, Rotter S. Autografting and PUVA: A combination therapy for vitiligo. DermatolSurgOncol 1992;18:357-60. |

| 10. Hann SK, Im S, Bong HW, Park YK. Treatment of stable vitiligo with autologous epidermal grafting and PUVA. J Am AcadDermatol 1995;32:943-8. |

| 11. Olsson MJ, Juhlin L. Repigmentation of Vitiligo by transplantation of cultured autologous melanocytes. ActaDermVenereol (Stockh) 1993;73: 49-51. |

| 12. Malakar S, Dhar S. Malakar RS. Repigmentation of vitiligo patches by transplantation of hair follicles. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:237-8. |

| 13. Olsson MJ, Juhlin L. Long-term follow-up of leucoderma patients treated with transplants of autologous cultured melanocytes, ultrathin epidermal sheets and basal cell layer suspension. Br J Dermatol 2002;147:893-904. |

| 14. Lahiri K, Malakar S, Sarma N, Banerjee U. Repigmentation of vitiligo with punch grafting and narrow-band UV-B (311 nm) a prospective study. Int J Dermatol 2005;45:649-55. 15. Malakar S, Lahiri K. Minigrafting for vitiligo. In: Gupta S, Olsson MJ, Kanwar AJ, Ortonne JP, editors. Surgical management of vitiligo. 1 st ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; p. 87-95. 16. Falabella R, Arrunategui A, Barona MI, Alzate A. The minigrafting test for vitiligo: Detection of stable lesions for melanocyte transplantation. J Am AcadDermatol 1995;32:228-32. 17. Malakar S, Dhar S. Treatment of stable and recalcitrant vitiligo by autologous mimiaturepunch grafting: A prospective study of 1,000 patients. Dermatology 1999;198:133-9. 18. Malakar S, Lahiri K. Punch grafting for lip leucoderma. Dermatology 2004;208:125-8 |

- Falabella R. Repigmentation of segmental vitiligo by autologous mimigrafting. J Am AcadDermatol 1983;9:514-21.

| 20. Malakar S. Punch Grafting. In: An Approach to Dermatosurgery. 1 st ed. Calcutta: A Paul, 1996. p. 44-6. |

| 21. Lahiri K, Sengupta SR. Treatment of stable and recalcitrant depigmented skin conditions by autologous punch grafting. Indian J DermatolVenereolLeprol 1997;63:11-4. |

- Malakar S, Lahiri K. Electrosurgery in cobblestoning. Indian J Dermatol 2000;45:46-7.

- Falabella R. Surgical treatment of Vitiligo: Why, when and how. J EurAcadDermatolVenereol 2003;17:518-20.

| 24. Malakar S. Dhar S. Rejection of punch grafts in three cases of herpes labialis induced lip leucoderma, caution and precaution. Dermatology 1997;195:414. |

| 25. Malakar S, Dhar S. Acyclovir can abort rejection of punch grafts in herpes-simplex induced lip leucoderma. Dermatology 1999;199:75. |

| 26. Malakar S. Lahri K, Successful repigmentation of six cases of Herpes labialis induced lip leucoderma by micropigmentation. Dermatology 2001;203:194. |

| 27. Lahiri K, Malakar S. Herpes simplex induced lip leucoderma: Revisited. Dermatology 2004;208:182. |

- Burge S, Rayment R. Free skin grafts. In Simple skin Surgery. 1st Mumbai: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1986. p. 71-84.